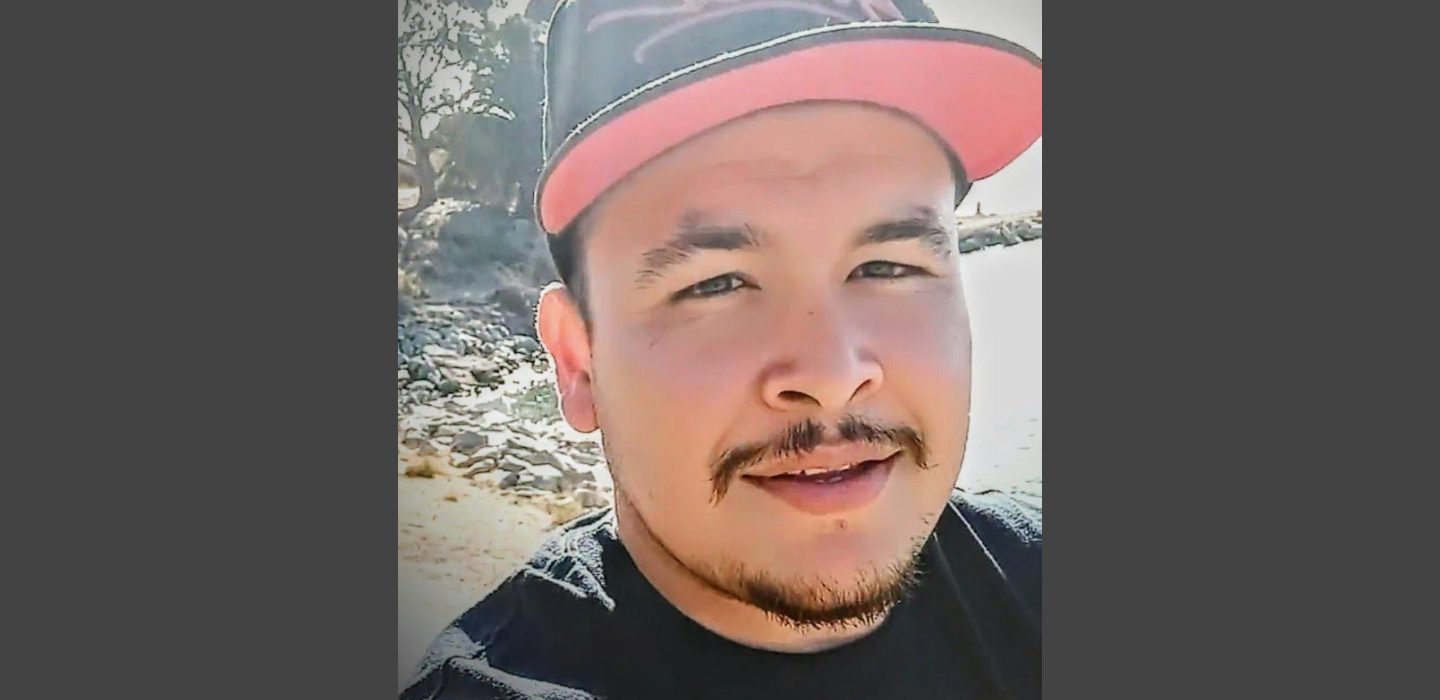

Adam Solorzano

This is the second in a series of essays highlighting graduates of our California Justice Leaders program, the first AmeriCorps program specifically for formerly incarcerated people. We’re excited to be co-publishing this series with the Prison Journalism Project to reach even more readers.

Leadership: The ability to inspire, motivate, guide,

and nurture others in service of a common goal;

having a vision and a pathway to achieve that vision.

I was anxious for weeks before I met a young man I’ll call JT who was wrapping up a six-year sentence in a youth prison. Because I know how hard it is to start fresh after years of drug abuse and being negatively impacted by both the justice system and the streets, the idea of helping someone emerge from the dark spaces in society felt like a daunting responsibility. What if I failed? A person’s future was at stake.

At home, I rehearsed different ways I might steer the conversation toward constructive life choices like trade school, or community college which was essential in changing my own life. When we finally met over Zoom, all that preparation went out the window. As soon as I began telling JT about me and my past, the conversation just flowed.

We spent most of that first meeting discussing all that we had in common: the limited opportunities and negative influences we each faced growing up: me in a small, rural California community and he in the city of Oakland. We talked about cycles of addiction and incarceration that affected our families over generations, the harsh realities of the legal system, and the fact of being poor and Mexican American in a country that expects you to fail.

Near the end of that first meeting, I got back to business, shifting to talk about what JT enjoys doing, what motivates and inspires him, and his goals for the future. Much to my surprise, he spoke passionately about helping others, especially his family and community. He told me he wants to coach youth football, help out in his father’s business, and eventually start his own construction company.

During our next meeting, it was my turn to surprise him. I gave him a detailed resource guide with practical steps he could take to move toward his goals. Stunned, he said, “No one has ever done anything like this for me. Thank you!” At that moment, I knew I had the capacity to help young people whom society has repeatedly failed.

JT wasn’t naïve. He understood the many barriers he would have to overcome. I reassured him that with a positive mindset he could achieve his goals. I knew it was possible because I had accomplished things that once seemed out of reach.

My youth was far from idealistic, but no less idealistic than most other kids in the small agricultural community of Westmorland, California, along the U.S.-Mexico border. Many of us were raised by single parents and had parents who were incarcerated. Many of us were using hard drugs, mostly methamphetamine, long before kids in better-off communities knew what meth was. I was an addict by 15, gang-affiliated and on probation by 16, and in jail by 18.

It took enormous willpower to change my life, and it took help. I was 23 when I finally got my high school diploma. When I enrolled in community college at the age of 25, I was reading at a third-grade level and had similar skills in math. I couldn’t follow much of the curriculum and didn’t even know what the word curriculum meant.

I was intimidated, sometimes literally scared, but determined not to give up. And knowing I couldn’t succeed alone, I asked for help. With support and encouragement from others, I eventually received my associate’s degree and later my bachelor’s from the University of California at Berkeley—drawn to Berkeley because of the university’s commitment to enrolling and supporting formerly incarcerated students.

At Berkeley, I also learned about California Justice Leaders, a partnership between AmeriCorps and the nonprofit Impact Justice, where I could use my own life experience to help young people like JT who were facing some of the same obstacles I had overcome with help from others.

This work is challenging. It takes more than resource guides. For example, during the end of my service year, I mentored a 22-year-old who had been incarcerated since he was 16 and had no idea where he would live when he was released in three months. Returning to his home community, he told me, “would not be safe,” and in any case, his family had essentially abandoned him, never once contacting him over the six years he was incarcerated. Understanding the importance of a safe place to lay your head at night, I helped him form a re-entry plan with housing at its core.

Over the course of my year of service in this first-of-a-kind AmeriCorps program, I was constantly reminded of how hard it is to move from the invisible margins of society toward the center, and what a difference it makes to have the support of others. Much like JT whose face lit up when he saw the resource guide I made for him, I was buoyed by a mother and grandfather who loved me, and by mentors and teachers who believed in me.

I no longer work as a re-entry mentor, but I’m helping to light the path for others by sharing their stories and my own. These are stories of people who have experienced some of the worst that life has to offer and emerged stronger–stories that rarely get told. I’m excited to be developing my skills as a writer as a Berkeley student once again, this time in the journalism master’s degree program.

Adam Solorzano completed his year of service as an AmeriCorps/California Justice Leader in March 2022. He is an active CJL alum and remains in contact with some of the young people he mentored. Adam received his bachelor’s degree from the University of California at Berkeley and is currently pursuing his master’s in journalism at Cal Berkeley.